Finding Your Roots

Anchormen

Season 9 Episode 9 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

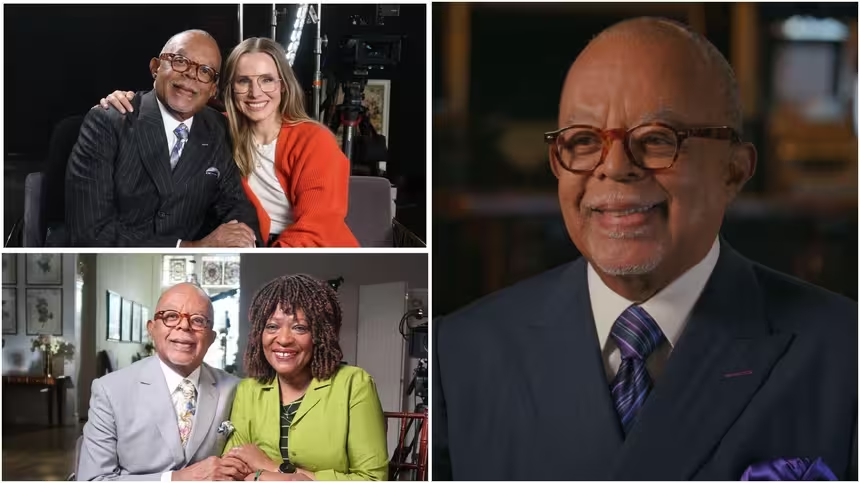

Journalists Jim Acosta and Van Jones uncover the ancestors who blazed a trail for them.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. introduces trail-blazing journalists Jim Acosta and Van Jones to the ancestors who blazed a trail for them, meeting runaway slaves and immigrant settlers who took enormous chances so that their descendants might thrive.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Anchormen

Season 9 Episode 9 | 52m 9sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. introduces trail-blazing journalists Jim Acosta and Van Jones to the ancestors who blazed a trail for them, meeting runaway slaves and immigrant settlers who took enormous chances so that their descendants might thrive.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to Finding Your Roots.

In this episode, we'll meet journalist Jim Acosta and political commentator Van Jones, two men with fundamental questions about their family trees.

ACOSTA: This is like turning on a light in a dark room.

I'm just learning about a world that I just never knew existed, and to some extent was not explored intentionally.

JONES: Never heard anything about it.

It's so sad because, you know, these people, they're living full lives.

They're getting up every day, they're doing stuff, they have dreams, they have ambitions.

And then, it just goes down the memory hole.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists combed through the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

ACOSTA: That's crazy.

GATES: It is.

ACOSTA: I didn't think there was any way in hell you were going to tell me that.

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a book of life... ACOSTA: Oh my gosh, this is incredible.

GATES: A record of all of our discoveries... JONES: What?

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

ACOSTA: You just don't know until you start scratching the surface, you know?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Your preconceived notions of what you think about yourself, where you came from, who you are doesn't mean squat unless you know the truth.

JONES: I feel like I owe them a lot.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: You know, you die twice, you die when your body dies and then you die the last time somebody says your name.

GATES: That's right.

JONES: So I'm gonna make sure that I keep them alive.

GATES: My two guests have covered some of the most important stories of our time.

In this episode, they're going to turn their focus inward, meeting people from their own families whose names they don't even know, and hearing stories that are important because they are so deeply personal.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes) ♪ ♪ GATES: There's more to Van Jones than meets the eye.

The former lawyer has been a CNN host and commentator since 2013, but he also spent three decades involved in civil rights activism, has written a best-selling book on green jobs, and even worked with the Trump administration on criminal justice reform.

It's a dizzying array of accomplishments, and Van traces them all back to a single source: his mother, a high school teacher, who was raised in the Jim Crow south, and taught her son to aim high.

JONES: I felt a responsibility to fight racism with excellence.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: That was the message.

My mom would tell me you're just as smart as those White kids.

You can do whatever you want to do.

I mean to me it was like a mantra.

I mean she would say it every day.

She says, "I'm teaching these White kids now.

I'm telling you, you're just as smart as the White kids.

You can do whatever you want to do."

One of the last conversations I had with my mother before she died, she said, I said, "Do you love me, Mom?"

She goes, "Yes, I love you."

I said, "Why?"

She goes, "Because you're not stupid."

(laughing) GATES: That's great.

You mean, Mom, if I had been stupid you wouldn't have loved me?

JONES: Maybe not.

Maybe not.

GATES: Oh, that's great.

While Van's mother was supportive, the world around him was decidedly less so.

Van grew up in Jackson, Tennessee, a small town where he often felt out of place, for a wide variety of reasons.

JONES: I was very shy.

I was very small.

You know, I was bullied.

I was made fun of.

I was, you know...Wedgies.

GATES: Mmm-hmm.

JONES: I would sometimes just go in the gym during the lunch breaks because it was empty.

And I would just go behind the bleachers and eat my food by myself because I didn't want to be teased and made fun of and just, all the little rough and tumble stuff.

I was a very sensitive kid... GATES: Mm-hm.

JONES: And um, I think it's part of why I am the way I am on television and other parts of my life is that I know what it's like to be misunderstood.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: I know what it's like to be laughed at.

I know what it's like to be left out.

I know.

I don't have to guess.

GATES: Van's salvation was his education, he left Jackson for the University of Tennessee, and excelled, his next stop was Yale Law School, which propelled him into the public sphere, setting him on the diverse paths he's been following ever since.

But Van has never truly left his hometown behind, to the contrary, his childhood experience still fuels him.

JONES: I do not, at this stage of my life, enjoy finding reasons to be angry and upset, even though I maybe should be angry and upset.

Maybe bad things are happening in the world.

It's true.

But for me, what I learned in that little, small town was that everybody counts, everybody matters, everybody has good days.

Everybody has bad days.

Nobody's the villain in their own movie.

GATES: Right.

JONES: Nobody's the villain in their own movie.

If you could understand their story you might be able to make a connection.

I've taken that through my whole career.

GATES: My second guest is Jim Acosta, the veteran CNN journalist who came to fame during the Trump era, when he battled with the president over a range of issues, from immigration to the first amendment.

Much like Van Jones, Jim is an idealist, with an old school passion for his profession.

ACOSTA: We're here to hold people accountable.

We're here to hold the powerful accountable.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Hold their feet to the fire, uh, speak truth to power.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Uh, they, they, those sound like corny things that journalists talk about, putting ourselves up on a pedestal and so on, uh, but it is what we're here to do.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: And if we're not doing it, what are the people in power gonna do?

GATES: Absolutely.

ACOSTA: They're gonna try to get away with e, with everything.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: And probably take the country down the tubes in the process.

GATES: Mm.

ACOSTA: Can't let that happen.

GATES: You've seen that close up.

ACOSTA: I saw that, I had a ringside seat for it.

GATES: Jim came to his "ringside seat" via a circuitous path.

he was raised in northern Virginia, not far from the Washington power scene he now covers, but in reality, a world away.

His father was a Cuban immigrant, his mother a local Washingtonian, they met as teenagers and split up when Jim was a child, leaving him to make sense of their relationship and his identity.

ACOSTA: I was an oops, my mom had me when she was 17 years old.

GATES: Oh my goodness.

ACOSTA: Yeah.

You know.

She raised me as a, as a single mom... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: While working her, in restaurants.

Um, my dad to his credit stayed in the picture.

You know, he moved to, uh, just a short distance away from where I was growing up, and, uh, I saw him on the weekends.

And so, in, you know, I had both parents, right?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: You know, they just weren't in the same house.

GATES: And, I bet she got grief for having a Cuban husband.

ACOSTA: Yeah, to the point where she, you know, she didn't really want... She didn't want any Spanish language around her, you know.

Nothing.

GATES: Sure.

No, right.

ACOSTA: It was two different worlds, you know?

English speaking world, White world Monday through Friday.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Saturday and Sunday, Cuban world.

GATES: Right.

ACOSTA: That's what... That was... That was my upbringing.

GATES: Jim's parents were so caught up in their own struggles that they didn't push him towards any particular profession, so Jim did it all on his own.

After college, he began working at local television stations, moving from Tennessee, to Chicago, to Dallas before ultimately landing a national correspondent's gig at CNN, where he's thrived.

It's been an extraordinary ascent, but Jim's never lost sight of where it all began.

ACOSTA: You know, I, always in the back of my mind I'm thinking, okay, what would my parents wanna ask?

What would they... GATES: Hmm.

ACOSTA: Wanna know?

What would the folks at my mom's bar wanna know, sitting on the bar stool?

What are they, what are they talking about?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: What do they care about?

And I, I also think, you know, there are a lot of critics, critics out there who say, "You guys in the elite media," and so on.

I'm like, "Wait a minute."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: My, my parents had me when they were in high school.

GATES: Right.

ACOSTA: My mom and dad worked in blue collar jobs.

I am far from... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: The elite... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Uh, in this country.

If anything, I think I came from the bottom up, and, you know, along the way you do learn a lot about life.

And I don't know, I would, I don't, I know for a fact I would not be here if it weren't for those lessons that I learned.

GATES: Jim and Van share similar occupations, but they also share something deeper.

They've been telling other people's stories for decades, while knowing only a fraction of their own stories.

It was time for that to change.

Each would now travel with me up branches of their family trees that they thought they knew, to uncover a reality that was far more complex than they'd ever imagined.

For Van Jones, the journey began with his maternal grandfather, Chester Kirkendoll.

Chester was a bishop in the Christian Methodist Episcopal church, and a towering figure in Van's childhood, in every sense of the word.

JONES: He was a giant.

He was tall.

I think he was like 6'3", 6'4".

And we would go to these conferences, these church conferences and uh, you know, my cousins and I, we'd be sitting there and, you know, kind of fooling around or whatever.

Then they would say we had the bishop's grandsons here.

Oh, crap.

GATES: Yeah.

JONES: And then my grandfather, please rise.

We'd stand up, you know, with our little, you know, clip-on ties.

Everybody's clapping.

Oh, we got the bishop's grandsons here.

We got the... now, you're scared to mess up.

Now, you have to sit there and be good.

GATES: You couldn't go to sleep.

JONES: Couldn't go to sleep.

Couldn't be, you know, teasing and acting crazy.

Uh, we were in awe of him.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: We were really in awe of my grandfather.

GATES: Though Chester was revered, the Kirkendoll's family history was not passed down.

Van suspected that his grandfather's deeper roots disappeared into the mist of slavery, but he knew nothing specific.

Moving back three generations, we came to a man named Mark Kirkendall.

Mark is listed by name in the 1850 census for Douglas township, Arkansas, living with his wife and children.

This was unusual because, at the time, almost no African Americans were listed by name in the federal census, enslaved people were listed only by age, color and gender.

JONES: Hum.

GATES: Van, what's that mean?

JONES: Does it mean they're White?

That means... GATES: No.

What's the only alternative?

They weren't slaves.

They were... JONES: Free people.

GATES: Free.

JONES: That's crazy.

So... GATES: Your Kirkendoll family was free 13 years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

JONES: I'm glad to hear that.

I had a hard time even getting my head there.

It didn't even occur to me that would be a possibility.

GATES: Of course.

And you had no idea?

JONES: Mm-mm.

GATES: What's it like to learn this?

JONES: You know, we've been here for a long time, all Black families.

We have some folks, you know, from Nigeria and Ghana and stuff now but most Black families have been here for a long time, and um... you just don't know what they all went through or what they were able to achieve.

Um... What they were able to overcome or not overcome.

You just don't know.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: And, um, so, you just kind of borrow these assumptions based on pop culture, based on roots, based on whatever you can grab.

Whatever you can, whatever little bits you can put together and mostly it's just imagination.

But just to know that somehow somebody in my family got free, somehow.

They didn't need, they didn't need Lincoln to free them.

GATES: No.

JONES: They got free on their own.

GATES: They did indeed.

JONES: Yeah, I like that.

GATES: Van wanted to know how his ancestors had won their freedom, and this led us to an incredible story.

In 1828, Van's third-great grandfather, Mark Kirkendall, was one of four enslaved people manumitted by the will of an Arkansas farmer named Joseph Kuykendall.

But the will contained a catch.

It decreed that Joseph's slaves would not be granted their freedom until they paid $800 to his sons, so after Joseph's death, Mark remained in bondage, working for the Kuykendall's.

And this arrangement did not end well.

JONES: "Murder.

We understand that Benjamin Kuykendall was shot last week by Mark, one of the slaves recently emancipated by the will of the late Joseph Kuykendall, and died in about three-quarters of an hour.

The Negro made his escape but was pursued and taken last night a few miles below this place."

What?

(laughing) What?

He's out here gun slinging?

GATES: Can you believe that?

JONES: That's an unexpected plot twist.

GATES: Though this article describes Mark as being "emancipated", that technically wasn't true, he had not yet paid off his $800, so, legally, he was still enslaved, and now he was in jail for killing a White man, many African Americans in his position would have been lynched, but Mark was not about to let that happen.

JONES: "A murderer escaped.

Mark, the Negro man who recently killed Mr. Benjamin Kuykendall in this county effected his escape from the jail in this place on the evening of the 30 of July.

He had been very heavily ironed by the sheriff but these he contrived to saw off with a case knife with which he was furnished by some person outside the jail and someone watched an opportunity when the sheriff and his wife were both absent to unlock the door.

The keys of which had been carelessly left in plain sight."

Oh, sookie-sookie now.

GATES: Your ancestor escaped.

JONES: Man, my ancestors be doing real stuff, man.

GATES: This is like a movie.

I mean this is better than any Black history movie out of Hollywood that you've ever seen, right.

JONES: That's crazy.

You think he like... Who knows what happened but I'm going to say, you know, in self-defense he killed this dude.

They locked him up.

He got himself free and he had a whole conspiracy.

GATES: What are you feeling right now?

This is real.

JONES: I know.

This is crazy.

I, um, uh, well... A, I'm glad he escaped.

GATES: Mm-hmm JONES: I don't know.

I just, part of what I think is inherent to being Black in America is this hope that you can beat the odds.

That you know the odds are against you but that there's some way that you can beat them.

GATES: Right.

JONES: That's where the soul and the drive and the pain and the pride all come from is going up against the odds.

GATES: Yeah.

JONES: And um... he went up against the odds and won, it looks like.

I'm scared to turn the page, but right now my family winning.

GATES: Mark's winning streak would soon come to an end.

He was caught in Louisiana, returned to Arkansas, and put on trial for murder, a capital offense.

But Mark still had luck on his side.

The jury convicted him of manslaughter, a lesser charge, likely with the encouragement of the surviving Kuykendall brothers.

Their reason?

Money.

The brothers still owned Mark, so a manslaughter conviction would preserve their property, whereas Mark's execution would leave them with nothing.

JONES: This is a barbaric society we're describing, man.

It's like we would kill you but we own you.

GATES: Yeah, exactly.

They say we ought to kill him.

Well, if they kill him.

JONES: You killed my brother but if I kill you then I don't get the money that I would have gotten.

GATES: Right.

JONES: Wow.

That's crazy.

GATES: This story was about to grow even crazier.

following his conviction, Mark was sentenced to three years in an Arkansas prison.

But he didn't stay in prison for long.

Van, this article was published in the Arkansas Gazette on June 29, 1830.

JONES: Hey.

Man, don't mess with my family.

That's all I'm going to let you all know right now.

What?

GATES: Would you please read the transcribed section?

JONES: The Negro fellow Mark be doing things, man.

"A pardon.

The Negro Mark, who has been confined in jail this place for more than the past year has received a pardon from the Governor and been discharged from prison."

What?

Man, Mark ain't nothing to mess with.

I'm letting you know right now.

Look, ya know, I work on pardons myself.

I've been fighting to free people from jails, too.

So, I, I...

But not like this.

GATES: You didn't know the origin of that impulse.

JONES: Exactly, I didn't know the origin of the impulse.

This has been waiting to come out of my DNA for centuries.

GATES: We have no idea why Mark was pardoned.

The governor may have had some sympathy for him, or the Kuykendall brothers may have persuaded the state to give them back their property, whatever the reason, after his pardon, Mark was returned to his former owners, and was once again enslaved.

But Van's ancestor had a final trick up his sleeve.

A notice published in an Arkansas newspaper reveals that Mark and three others escaped en masse from the Kuykendall estate, and this time, Mark stayed free.

JONES: They ran off again.

GATES: Ran off again.

Isn't that amazing?

It's astonishing, really.

JONES: Yeah, man.

GATES: What's it like to know this guy is your direct antecedent?

That you are his direct descendant.

JONES: Well, I have a lot to live up to but, um, I like this guy a lot.

Look, I mean these are real human beings just like anybody watching this show.

Like, what would you do, you know?

Like, would you just sit around and just be enslaved and try to like it and hope in 300 years Dr. King's going to come around and give a speech?

You know what I mean?

People fight for their freedom and we're still fighting for our freedom.

But I feel very proud of him.

This dude is...

The Negro fellow Mark ain't nothing nice, ain't nothing to play with.

GATES: What are you going to tell your kids about this?

JONES: I'm going to tell my kids they come from a real serious line of freedom fighters, you know.

Uh, and people who fought with what they had.

Uh, I don't know.

The guy had a file, somebody slipped him a file.

He didn't file his fingernails.

He's filing the chains off.

You know what I mean?

You fight with what you have.

GATES: Yeah.

JONES: Uh, and you, um, you get your family to a place where they can thrive.

GATES: Unlike Van, Jim Acosta knew exactly where his roots lay, but he had no access to those roots, because his parents had turned their backs on them.

We started on Jim's father's side, where the reason for this decision was political.

Jim's father, Abilio Jesus Acosta, was born in Cuba in December of 1950.

Abilio was nine years old when the Cuban revolution threw his country into chaos, and, just three years later, he and his mother fled for the United States, leaving everything behind.

Jim was able to get a sense of just how much had been lost when he and Abilio visited Cuba in 2016, and Jim saw his father transformed.

ACOSTA: It almost felt like he became, um, an 11-year-old kid again.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: You know?

Here he was in Havana, you know, roaming these streets with me, and he was, uh, pointing out, um, his childhood memories, you know?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: He was not looking back at these memories as someone who recalls all, all of this as a man.

He was re, remembering these things from when he was a boy.

GATES: Right.

ACOSTA: And, you know, we went out to, uh, the town that he grew up in, uh, Santa Maria de Rosario.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: And, um, he, uh... We, we walked up to, uh, his relative's house.

He kind of knew the way.

GATES: Hmm.

ACOSTA: And, uh, they... A couple of them were sitting on the doorstep and there was this, uh, older woman on the doorstep.

I, I think she was one of his cousins.

And, she immediately knew who he was.

GATES: Oh, my God.

ACOSTA: E-even though he hadn't been back in 50 years... GATES: Amazing.

ACOSTA: Uh, more than 50 years.

54 years.

She, she screams out, "Abelito."

GATES: Huh!

ACOSTA: And she, she recognized the 11-year-old boy that used to... GATES: Hmm.

ACOSTA: Roam the streets of that little town.

GATES: That's astonishing.

ACOSTA: It's astonishing to me, but she knew exactly what... Brought us inside.

We had to sit down, uh, with all of them.

Everybody was in tears.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: And, um, it was, uh...

It was just a mind-blowing experience.

I felt like I was, you know, traveling through time with my dad.

GATES: Though the visit was heart-warming, it could not restore all the family history that had vanished in those 54 years, so Jim came to me knowing almost nothing about his Cuban roots.

We were able to rectify that...

Taking him back to his fourth great-grandparents, both of whom were born in the early 1800s in the same small town that he'd visited with his father.

ACOSTA: Wow.

GATES: This makes six generations of your family who lived in Santa Maria Del Rosario, all the way down to your daddy.

ACOSTA: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to know that you have such deep roots in that one place?

What's that feel like?

ACOSTA: It's, it's remarkable.

It makes me think, I guess I have a homeland.

GATES: Yeah.

ACOSTA: Because I mean I, I had friends growing up who would say, "Well, we're first Virginians", you know, or, "You could trace our ancestors all the way back to the 1800s or 1700s in Virginia", blah blah.

And I didn't have that.

GATES: You do now.

ACOSTA: I do now.

GATES: Jim would soon have even more.

We were able show him primary documents revealing how his ancestors lived in Santa María del Rosario, including census records showing that they leased a small farm and a marriage certificate recording the day they wed. ACOSTA: Beautiful.

It's just incredible.

It's just so, so amazing to see all of this laid out, um...

I can't believe it, I can't believe it.

GATES: Your fourth great grandparents were married on September 10th, 1842 in Santa Maria Del Rosario, and...

There, you could see a photo of the church.

ACOSTA: Amazing.

Just incredible.

And I've been to this church, I went inside.

GATES: Oh, you did?

ACOSTA: I've been inside this church, it's a beautiful old Spanish church.

And I remember, they do have a lot of records there, so I-I didn't realize... Not this extensive, I didn't know it was this extensive.

This is remarkable.

GATES: As it turns out, the records we found in this church were just the beginning, we were able to trace Jim's father's family from Santa Maria del Rosario back across the Atlantic to the Canary Islands, which lie off the coast of Africa and which were colonized by Spain in the 1400s!

We even found a document that details why Jim's ancestors left these islands for Cuba.

ACOSTA: "On this day, and in said City of Santa Maria del Rosario, His honor, The Count, manifests the 30 families to which he is obliged to settle the new city, so their names will be known for all time.

The families are the Alferez Mayor.

Alferez Mayor."

GATES: Mayor.

Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: "Don Gregorio Yanez, the Rehedor Don Cristobal Fundora."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: "Bernardo Caraballo de Villa Vicencio."

GATES: Yeah.

ACOSTA: "Al Calde De La Santa Hermandad."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: "Salvador Hernandez Pilotto and Joseph del Pozo."

GATES: Do you know what this means?

Do you know what you just read?

ACOSTA: These are the original settlers.

GATES: These are the founders.

ACOSTA: The founders.

GATES: Of the town of Santa Maria del Rosario.

ACOSTA: Wow.

GATES: Jim.

ACOSTA: Are you kidding me?

GATES: Your family founded the town of Santa Maria del Rosario.

ACOSTA: Is that right?

Wow.

GATES: They didn't just live there, they founded the town.

ACOSTA: That's crazy.

And when I went there, I found them living in absolute poverty.

GATES: Yeah.

ACOSTA: And their ancestors, my ancestors, started this town.

GATES: Right.

I wonder if they even know.

ACOSTA: I don't think they know.

I'm sure they don't know.

GATES: Jim has at least five ancestors who helped found Santa María del Rosario.

It was hard to understand how their accomplishments had been forgotten, but as we dug deeper into the archives, we saw that the family's story was far more complicated than it seemed.

Would you please read the translated section?

ACOSTA: Oh goodness, here.

GATES: Yeah.

ACOSTA: I can already see it.

"Name of owner, Don Julian Yanes.

Female slaves, one."

GATES: Female slaves, one.

ACOSTA: Wow.

GATES: Jim, your ancestor held a woman in slavery.

Did you ever imagine that anyone in your family in Cuba had been a slave owner?

ACOSTA: No idea.

No idea.

And um, I have to say, I, you know, I guess, I, I, I'm ashamed that one of my ancestors owned another human being.

GATES: Mmm.

It had never occurred to you that this was possible?

ACOSTA: No.

I mean, not...

Growing up with parents who were working themselves to death to make ends meet for me, just to put food on the table, I wouldn't think in a million years that any ancestor of mine would own another human being.

GATES: Historically, slavery played a huge role in Cuba's economy.

Beginning in the mid-1500's, and continuing until the slave trade was abolished in 1867, the island imported about 980,000 enslaved human beings, more than twice as many as the United States.

And we learned that at least three other ancestors on Jim's father's side held no less than ten enslaved people between them.

A discovery that compelled Jim to rethink this branch of his family tree.

ACOSTA: Wow, I wish I had known about it sooner.

Um, you know, to think that I made it all this way through life and not known that there was this...

Unfortunate chapter in my ancestor's history, um, I guess, to some extent, I wish you hadn't told me that.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Because I, of who I am and my belief system and what I think and what I believe, um... and the way I think about our country, but why not me?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Why not, why, why can't that be my story?

GATES: We'd already traced Van Jones' maternal roots back to the early 1800s, turning to the paternal side of his family tree, we weren't able to go as far into the past, but the stories we uncovered were no less powerful.

Van's father, Willie Jones, was an Air Force veteran who served in the Vietnam war, and Van vividly recalls his extraordinary strength.

But that strength was born of a deep pain.

Willie lost his own father to cancer when he was a boy, an experience that molded him to his core.

JONES: Apparently they were very close, as I understand it, my grandfather was a working guy, like a skilled laborer... GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: And he would have my father come with him to do certain things and to be a part of certain things.

He just loved my father.

And then my father, um, says one day he went to talk to his dad and his dad said I'm not going to be here and you're going to have to be the man of the house.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: And very shortly after that, my grandfather died.

GATES: Mmm.

JONES: And, you know, my father, I think took really seriously what his father told him that he is the man of the house even though he was a little kid.

And he has to do right by his family.

He has to take care of the family.

Even when he went to the military he had all his money sent home to his mother.

He made his money by doing pool tricks and card tricks and stuff like that.

Everything was about his mother, his brother, his sisters.

Um, and uh... And even late in his life, uh, he would get choked up talking about his father.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: I don't think he ever got over it.

I think he just tried to deal with it.

GATES: This tragedy effectively severed Van's connection to his father's family.

He believed that his grandfather had deep roots in Tennessee.

But beyond that, this part of his ancestry was a blank slate.

We set out to fill it in, starting with his grandfather's birth certificate.

It lists his parents, Van's great-grandparents: Richard Jones and Alice Myers.

JONES: Oh wow.

GATES: Have you ever heard those names?

JONES: Never.

GATES: There's another person listed on that document.

Could you please read the name of the midwife who delivered your grandfather Walter?

JONES: Ella Meyers.

GATES: You ever hear of Ella Meyers?

JONES: No.

GATES: Well, Ella was Alice's mother.

JONES: Okay.

GATES: Ella's maiden name was Green and she was born around March 15, 1864 in Mississippi, likely into slavery.

Did you have any idea that you had roots in Mississippi on your father's side of your family tree?

JONES: No.

I thought we had been in Tennessee since we were enslaved.

I thought that's where we were enslaved.

GATES: Nope.

JONES: That's crazy.

GATES: Ella Green is Van's great-great-grandmother, and records suggest that Ella faced enormous challenges throughout her life.

In the 1900 census for DeSoto County, Mississippi, we found her and her husband working as tenant farmers, meaning that they didn't own the land they worked on.

What's more: by that time, Ella had already lost three children, and was raising six more.

These facts did not surprise Van.

JONES: You know, I knew that my dad's side of the family had a rougher road, a rougher path.

And so um, it makes sense to me that uh, they would have, you know, been working on the land and having a bunch of kids trying to make sure that at least some of them survive and all that kind of stuff.

You can see that strength in my dad's side of the family.

You can see that determination in my dad's side of the family.

GATES: Well, now you know where it comes from.

JONES: Yeah.

Absolutely.

GATES: We wanted to trace Ella's line back further, but we hit a wall.

The earliest record we could find for the Green family was the 1870 census for Mississippi, the very first census taken after emancipation, it lists Ella as a seven year old girl, living with her parents, Columbus and Julia Green.

Unfortunately, and unlike for your maternal ancestors, this is where the paper trail for your paternal ancestors ends.

JONES: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to learn this?

JONES: I mean, listen.

I think most people who watch your show know that if you're Black, because we were considered property, you know, it's like trying to find the title of a car... GATES: Yeah.

JONES: More than trying to find a human.

That's, that's the... that's how we were treated.

So, there is just like this big drop off.

You know that your people are from Africa.

You don't know from where.

You don't know what language they spoke or what religion they had.

You don't know how they got here.

You don't know where they landed.

All you know is that somehow you wake up in America where you know, you have a family history that has been obliterated and a present that is very, very challenging and a future that is unknown, and you have to figure it out from there.

And, you know, it's hard to have the fruit when you don't have the root.

GATES: That's true.

JONES: You know, when you don't know where you're from.

And I know people who are from more European backgrounds.

Oh, you know, I'm... you know my family came over here, like my grandparents came and it's a little bit fuzzy but it's fuzzy because y'all just didn't pay attention.

It's not fuzzy because somebody stole you and put you in a different context... GATES: Right.

JONES: Um, and mistreated you for a couple of centuries.

So, when something is lost, you feel different about it than when it's stolen.

When your history, family history is lost that's different than when it's stolen.

If you lose your watch you feel differently about it than if somebody steals it.

GATES: Though we'd exhausted the paper trail, we still had one more detail to share regarding Van's father's family.

It turns out that Van is not the only famous descendant of Columbus and Julia Green.

We actually had a guest in an earlier season of our series who connects to them as well.

JONES: Who?

GATES: You would never guess in a million years.

JONES: I probably would not guess in a million years.

I think I, I think I know most people in my family, and I don't think any of them have been on your show.

GATES: Okay.

One of them has.

You just didn't know he was in your family.

JONES: Who is it?

GATES: Please turn the page.

JONES: What?

I, I know this brother.

That is crazy.

GATES: Your cousin is Emmy and Golden Globe Award winning actor Sterling K. Brown.

JONES: That's nuts.

We're cousins?

GATES: You are cousins.

You are definitely cousins.

JONES: I want some money!

(laughing) GATES: Van and Sterling are fourth cousins, and this discovery was especially exciting to us because we initially made the connection using DNA, and then we confirmed it with documents that show exactly how the two men are related.

JONES: So Columbus Green and Julia Green... GATES: Are your third-great-grandparents.

JONES: Right.

And they had a daughter named Ella and a son named Robert.

GATES: Yeah.

JONES: And from there you get, from Ella you get Van Jones and from Robert you get Sterling K. Brown.

GATES: Isn't that cool?

JONES: That's unbelievable.

GATES: Unbelievable.

JONES: That's crazy.

Well, I don't even know what to say.

I mean literally the last time I saw Sterling K. Brown we were at a...

I think a BET Award show.

Walked over to him, shook hands.

He knows my work.

I knew his work.

We were texting for a while.

I mean I literally know this guy.

GATES: Isn't that cool?

JONES: That's so crazy.

That's amazing.

GATES: Turning back to Jim Acosta, we moved from his father's native Cuba to a place that was far more familiar.

Fairfax, Virginia where Jim was raised by his single mother, Barbara Ellen Rice, a woman whose character left an indelible mark on her son.

ACOSTA: My mom raised me with an iron fist and, uh, you know, she would say, uh, "If you ever smoke a cigarette, if I ever catch you smoking a cigarette, I'll make you eat the whole pack."

You know?

Uh... "If you have an earring in your ear, I'm going to rip it out."

You know?

"I want your hair high and tight."

GATES: I love your mom.

ACOSTA: You know, that was how she raised me.

She, she was raising a boy on her own to become a man and she wanted him to be tough.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: So, she was tough.

GATES: Barbara's toughness was almost certainly inherited, but Jim knew little about its source because his mother rarely spoke about her roots.

We set out to change that, starting with the passenger list of a ship that arrived in New York City from Queenstown, Ireland in August of 1905.

Onboard, Jim's great-grandmother, a very determined young woman.

ACOSTA: Annie Snee, housekeeper, nationality, Ireland.

Last residence, Coolaney?"

GATES: Coolaney.

ACOSTA: "Coolaney.

Final destination, Jersey City.

Passage paid by self."

GATES: Your great-grandmother was just 20.

She's listed as a housekeeper, and she has no money.

You could see a photo of the ship.

ACOSTA: Wow.

This is it right here.

GATES: How does it make you feel to see that?

ACOSTA: Makes me proud.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Makes me proud.

It's beautiful.

GATES: This record shows that Jim's great-grandmother came from an Irish village called Coolaney... At the time, upward mobility for young women in rural Ireland was virtually non-existent, and Annie likely immigrated to America in search of opportunities she could never have found at home.

She got more than she bargained for.

We found her in the 1910 census for New York, working as a servant in what would be one the most glamorous buildings in Manhattan well into the 1970s.

ACOSTA: "Annie Snee, servant, 26, private family."

GATES: There's Annie working as a live-in servant for a woman named Josephine Tailor, and you can see a photo of the apartment building in which she was living on the left.

Do you happen to recognize that building?

ACOSTA: I was gonna say, that looks like a famous building.

Is that the Dakota or?

GATES: That's the Dakota, baby.

ACOSTA: That is the Dakota, baby.

GATES: Your great grandmother was living in the Dakota, the famous apartment building that was home to Judy Garland, Lauren Bacall, and John Lennon.

ACOSTA: John Lennon.

GATES: Uh, what's it like to learn that?

ACOSTA: That is, that's wild.

That is, 'cause I... As soon as I saw that building, I thought, "Why is there a picture of the Dakota in here?"

'Cause I, as somebody who's lived in New York and obviously, John Lennon and everything else, I, I recognized that building.

GATES: Yeah.

ACOSTA: Fascinating.

GATES: Annie found herself in New York City at the tail end of the Gilded Age, and she made the most of it, she would soon marry Jim's great-grandfather, a chauffeur named Herbert Rice, and the couple would end up raising five children in a home of their own on the upper east side of Manhattan.

But as we looked closely at the records that Annie left behind, we found something back in Ireland that suggests her journey was more complex than we'd imagined.

This is a record from Coolaney, um, dated March 9th, 1911 about one year after the census on the last page.

Would you please read the transcription?

ACOSTA: Uh, "Patrick Joseph Rice, date and place of birth: March 9th, 1911, uh, from Creevaun."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: "Mother: Anne Rice, formally Schnee.

Father: Herbert Rice.

Dwelling place of, uh, father: New York."

GATES: Just one year after Annie was recorded on the 1910 US census, she gave birth to a son, your grandfather's brother but back in Ireland.

ACOSTA: Wow.

GATES: And she listed her name as "Anne Rice," your great grandfather Herbert's last name.

So, why do you think Annie returned to Ireland to give birth?

Any theories?

ACOSTA: No, I have no idea.

That is strange.

GATES: Curious, isn't it?

ACOSTA: Yeah, curious.

GATES: Oh, let's find out.

ACOSTA: Let's find out.

GATES: Will you please turn the page?

ACOSTA: Okay.

GATES: Jim, this is a record from Mount Vernon, West Chester, New York.

It's dated August 26th, 1911, five months after the record on the last page.

Would you please read the transcription?

ACOSTA: "Affidavit for license to marry.

Groom: Herbert Rice, 28, chauffeur.

Bride: Annie Schnee, uh, 26, waitress."

GATES: She's applying for the right to marriage five months after the baby was born.

ACOSTA: Ah.

GATES: So, Jim, you know what this means.

ACOSTA: Yeah.

GATES: Her son, your great uncle Patrick, was born out of wedlock.

ACOSTA: Yeah.

GATES: And she went back there.

So nobody would know.

ACOSTA: Oh, wow.

GATES: To be discreet.

Annie listed Herbert as her husband on his birth certificate in Ireland, but they weren't married.

ACOSTA: I see.

GATES: So, she was making it all look right.

ACOSTA: Yeah.

So interesting.

GATES: Turning from Annie to her father, a man named Daniel Snee, we were able to add another chapter to this story.

Daniel is Jim's great-great-grandfather.

He was born in County Sligo sometime around 1840.

His father, James Snee, was a farmer in that same county, meaning that when Daniel was a child, he and his family endured a terrifying ordeal.

In 1845, Ireland's potato crop began to fail, precipitating one of the worst famines the world has ever known.

More than one million Irish people died either from starvation or from disease.

ACOSTA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: In County Sligo alone, nearly one-third of the population vanished in the decade between 1841 and 1851.

A third.

ACOSTA: Wow.

GATES: So how do you think your ancestors managed?

They almost certainly saw friends, neighbors, and relatives die.

ACOSTA: Uh, it, it would seem to me that it was pretty ingrained in them, um, suffering, and suffering that was going on during this time period.

I, I would imagine it was a pretty searing experience.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

Oh, it's unimaginable.

ACOSTA: Yeah.

GATES: I mean, one-third?

ACOSTA: Yeah.

GATES: To imagine one-third of your... ACOSTA: People starving to death.

GATES: Yeah.

Just disappearing in a decade.

ACOSTA: And it's heartbreaking.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: It's heartbreaking to think that my ancestors had something to do with that.

GATES: The famine devastated Ireland for generations, creating poverty that likely contributed to Annie Snee's decision to leave her home and family for a new start in America.

But as we surveyed Jim's mother's roots, we discovered that Annie wasn't the only member of her family to make such a bold decision.

Jim has a half-dozen ancestors from Ireland, England, and even what is now the Czech Republic, who boarded ships and passed through Ellis Island in search of a better life.

Seeing their journeys laid out, renewed Jim's faith in his own work.

ACOSTA: People know who I am because I stood up to Trump.

When it came to immigrants and I can't tell ya how many times I run into people from all walks of life, all around the world, who are grateful for that.

And I did it, not knowing the full history.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: Which you've given to me, but knowing a little bit about myself, you know, as a human being, that I came from this immigrant experience and I was, you know, uh, a Cuban-American, an Irish-American... and a little bit of Czech.

Um, and all of these forces came together to make who I am.

GATES: Indeed.

ACOSTA: And so how can I sit here silently as somebody is denigrating that entire experience.

When I know full well, being an educated person... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: That is very much part of the fabric of this country.

GATES: Will you ever look at the Statue of Liberty in the same way again?

ACOSTA: Um, not, no way.

No way.

I was always fond of Lady Liberty, but now there is a special bond, a special connection.

GATES: Yeah.

ACOSTA: No question about it.

GATES: The paper trail had run out for Jim and Van.

It was time to unfurl their full family trees... ACOSTA: Oh, my goodness.

GATES: Now filled with ancestors whose names they'd never heard before... JONES: Oh, wow!

GATES: For each, it was a moment of awe... A chance to see how their own lives had been shaped by the women and men who came before them.

JONES: I feel like I owe them a lot.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

JONES: I feel like I owe them a lot.

I feel like I owe, you know, people, you die twice.

You die when your body dies, and then you die the last time somebody says your name.

GATES: That's right.

JONES: So, I'm going to make sure that I keep them alive.

GATES: Nobody has to do this research again.

(sniffle) ACOSTA: Thank you.

Thank you.

They went through a lot to get here.

GATES: My time with my guests was nearing its end, but I had a final question for each.

I wanted to know how learning the stories of their ancestors had affected the way they thought of themselves as Americans.

For Van, the experience had confirmed his deepest beliefs.

JONES: I've been telling people that this is our country.

I don't understand what people are talking about.

My family's been here for...

I can document now at least seven generations.

GATES: Right.

JONES: I've got folks who just got off the boat.

My grandparents came here.

My parents came here.

Great, welcome, but I've always felt that African Americans should be much more, um, proud and make a bolder claim that this is our country.

Um, if, you know...

The Native Americans got a first claim.

We got second because there's very few families that have been here as long as mine.

GATES: That's true.

No Ellis Island for your ancestors.

JONES: Absolutely.

GATES: Unlike Van, Jim's family tree is filled with recent immigrants, and this compelled him to see a larger lesson for our country.

ACOSTA: If we're gonna make it as a society, and that the verdict is not exactly in yet.

GATES: Right, right.

ACOSTA: We are gonna have to treat each other like brothers, like sisters.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ACOSTA: And what this tells me is that you have no idea who those brothers and sisters are.

GATES: It's true.

ACOSTA: And where they come from.

GATES: Right.

ACOSTA: And what life experiences they come from.

So, it behooves you... GATES: Right.

ACOSTA: To be a good human being to those folks.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Jim Acosta and Van Jones.

join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of Finding Your Roots.

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S9 Ep9 | 32s | Journalists Jim Acosta and Van Jones uncover the ancestors who blazed a trail for them. (32s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: